Buy This Book

“There will come a day when these girls will no longer be a part of your life, and you’ll no longer care about what they once said about you,” Elaine DePrince. —Taking Flight

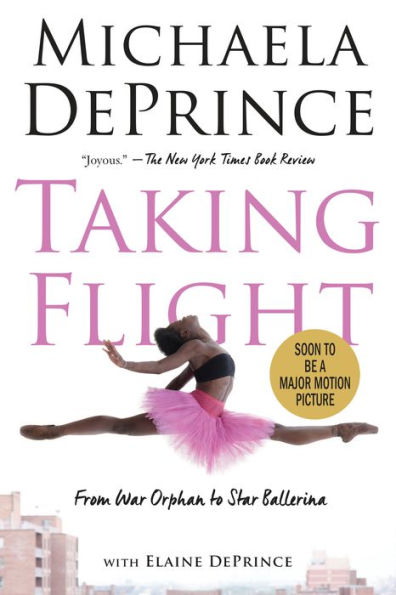

Taking Flight: From War Orphan to Star Ballerina

by Michaela DePrince & Elaine DePrince

AR Test, Diverse Characters

12+

Score

6.3

256

Professional ballerina Michaela DePrince hasn’t always lived in the world of ballet. Adopted from war-torn Sierra Leone when she was young, her life was forever changed by her adopted family and a picture of a ballerina, ripped from a magazine, floating in the wind. Upon seeing that ballerina, ballet became DePrince’s love. Taking Flight is DePrince’s memoir of her life as a war orphan who became a professional ballerina in the United States.

Taking Flight begins with many of DePrince’s memories of her native country of Sierra Leone, which was experiencing a destructive civil war. DePrince’s recollections of events are often harrowing. Her birth parents, who were clearly a shining light in her life, died in quick succession due to events surrounding the civil war. She talks about the orphanage that her uncle dragged her to, and the terrible treatment of the children there. However, DePrince’s narration shows that despite the terrible situation, she was still bright and animated, making friends with the other children and making up games.

Much of the story describes DePrince’s experiences in ballet after the DePrince family adopted her with a couple of the other girls from the orphanage. Family is an important feature of her story and considering her earliest memories, it is a relief to watch her life improve thanks to her jovial spirit and the loving people in her life.

DePrince, being a professional ballerina, talks a lot about ballet. When she describes seeing the Nutcracker with her family and eventually performing in various productions of the show, the reader can feel the love she has for her chosen profession. Not all that glitters is gold, however. DePrince also addresses the extreme lack of diversity in the ballet world, and her own struggles being a black ballerina. She sometimes describes comments from other parents, ballerinas, and instructors about her race and how it affects or will affect her dancing in the future.

Despite these obstacles, despite the odds, DePrince is a professional ballerina living well in the United States with her loving family. DePrince ends the book by discussing how she hopes she can be a role model for other aspiring ballerinas and how she wants to help other people affected by war in their home countries. Taking Flight oozes DePrince’s love for ballet and her family. It is a wonderful and wondrous thing that DePrince found a picture of a ballerina that day in Sierra Leone, jump-starting the rest of her life. This book will appeal to people who like dance as well as people looking for a book about overcoming adversity. DePrince had the odds stacked against her, and her story is inspiring for people from all walks of life.

Sexual Content

- The critics discuss Michaela DePrince’s Odile in Swan Lake, “She was the sweetest seductress you ever saw . . . but she has yet to develop any ballerina mystique.” DePrince discusses how she needed to become mysterious and a “seductress” in the role.

- Michaela says of her boyfriend Skyler, “I was lucky enough to fall in love with a young man who was capable of doing all the things my mother had described to me.”

Violence

- DePrince’s Uncle Abdullah had three wives and fourteen children, and DePrince says at night they could hear Uncle Abdullah “beating his wives and daughters . . . He blamed any and all of his misfortunes on their existence.”

- DePrince is originally from Sierra Leone, where a civil war has been brewing since 1991. “As the war progressed, the youth lost track of their goals and started killing innocent villagers.”

- A man came to DePrince’s family “moaning and wailing. He told us that he was the only survivor of his village. The debils (rebel forces) had forced him to watch as they killed his friends and family. Then, laughing, they asked if he preferred short sleeves or long sleeves. He said that he usually wore long sleeves, so they cut off his hand and sent him on his way to spread fear and warnings throughout the countryside.”

- The debils shot and killed DePrince’s father while he was working in the mines. DePrince describes, “I woke up to the sound of my cousin Usman’s voice. ‘Auntie Jemi,’ he hissed quietly. ‘Auntie Jemi, the rebels came to the mines today. They shot all of the workers.’”

- DePrince’s mother refused to marry Uncle Abdullah, which angered Uncle Abdullah. He abused both DePrince and her mother, starving them. DePrince says, “We often went hungry, and for months Mama gave me most of her food.”

- DePrince’s mother dies of Lassa fever. DePrince notes that “Most of the night I had heard Mama tossing and turning. Just before dawn I heard her sigh loudly three times and finally grow quiet.” DePrince did not realize that her mother had died, and instead thought that her mother had finally fallen asleep.

- Within a couple of days of both of her parents dying, DePrince ends up at the orphanage, where “If [DePrince] awakened Auntie Fatmata (one of the workers) with [her] crying, she will beat [DePrince] with her willow switch.”

- Another girl was going to be whipped in the orphanage for wetting her mat, but DePrince steps between the girl and the worker and tells the worker that the punishment is unfair. As a result, “Auntie Fatmata raised her switch and struck [DePrince] first and then Mabinty Suma. She struck us over and over again, raising welts all over our bodies.”

- It is noted that in the orphanage, the “aunties loved to tug on our tightly braided cornrows, because it hurt so much but left no evidence of their abuse. This was important to them. Andrew Jaw needed to send our pictures to America, so he did not want to see bruises on us.”

- In order to make DePrince cry, Auntie Fatmata “ground chili peppers into a fine powder” and “sprinkled it all over [DePrince’s] face until it filled my nostrils, eyes, and mouth.”

- When most of the children in the orphanage contracted malaria, Auntie Fatmata made “one of the younger children go to the bathroom on [DePrince’s] hair and face while [she] was asleep.”

- DePrince’s teacher, Sarah, is killed by the debils, and they cut her unborn baby out of her body. One of them, “slashed downward with his knife and cut into Teacher Sarah . . . The debil reached inside of Teacher Sarah and pulled out her unborn baby.” The nightwatchman, Uncle Sulaiman, saves DePrince. It is assumed that the baby died.

- The director of the orphanage “beats [DePrince] with a switch for leaving the orphanage.”

- When they are forced to walk into the jungle, DePrince and the other orphans, “saw hundreds of dead bodies on our way out of Sierra Leone. The debils had taken machetes to many of the people, but the majority of them, even small children, had been shot in the head. They lay sprawled on the ground with their eyes and mouths open in terror.”

- DePrince vomits on herself and Uncle Ali out of nervousness on the plane ride to Ghana. Uncle Ali “dragged [her] into the toilets and spanked [her] soundly before bringing [her] back past everyone a second time.”

- DePrince’s new mom (Mama) made a list of rules for DePrince and her sister. They were, “No hit, no bite, no pinch, no scratch, no say caca.” They soon stopped doing those things, except to their dolls because they were “mimicking the way Auntie Fatmata had treated the children in the orphanage.”

- DePrince notes a statistic about Sierra Leone. She says, “More than 90 percent of girls in Sierra Leone endured genital mutilation.”

Drugs and Alcohol

- As a child in Sierra Leone, DePrince had contracted a form of mononucleosis and had not recovered from it, leading to an infection five years later in her left eye. The doctor “put [her] on an antiviral drug.”

- While attending boarding school, some of the older high school students taught DePrince “that alcohol mixed with a power drink would relax [her] muscles, relieve the stress of Auntie Fatmata, and ease the pain of tendinitis. Someone suggested I try it once when I was off campus, and I did and never tried it again because it made me violently ill.” Some other students suggest fad diets, smoking cigarettes, and “taking laxatives and vomiting after meals.”

Language

- Uncle Abdullah is extremely sexist and uses plenty of sexist language. For instance, he says of DePrince, “All she needs to learn is how to cook, clean, sew, and care for children.”

- Uncle Abdullah tells DePrince’s father that DePrince, “needs a good beating.” He then says about DePrince’s mother, “And that wife of yours, she too needs an occasional beating. You are spoiling your women, Alhaji. No good will ever come of that.”

- DePrince and her adopted sisters experience racism in the United States. Once when she and one of her sisters were having a tea party on the lawn, “a neighbor walked over and said, ‘You girls will need to take your things and move your tea party out of sight of my property. I’m trying to sell my house. Someone is coming to look at it, and I don’t want them to see the two of you.’” DePrince describes these experiences over the course of a chapter, and some more stories are littered throughout the novel as well.

- DePrince notes that “unless I’m in physical danger or my civil rights are being violated, I ignore [bigotry aimed at DePrince]” except for the “racial bias in the world of ballet.” DePrince spends a chapter explaining some of the things parents, other dancers, and dance coaches said about black dancers. In one incident, “one of the mothers who was chaperoning us said, ‘Black girls just shouldn’t be dancing ballet. They’re too athletic. They should leave the classical ballet to white girls. They should stick to modern or jazz. That’s where they belong.’”

Supernatural

- To get revenge on Auntie Fatmata, DePrince pretends to be a witch and have “voodoo powers.” She does this by rolling her eyes back into her head and turning her eyelids inside out, saying, “I am a witch. I will place a spell on you if you harm me.” She then says, “The aunties were superstitious, and we lived in a place where many people practiced voodoo, so I knew my trick would scare them.” They never again physically abused her.

- While working as an apprentice on a touring company for The Nutcracker in New England, DePrince lived in a house with other ballet dancers. She and the other dancers thought that the “Victorian house looked and sounded haunted,” and DePrince confesses to being afraid of “getting up to go to the bathroom at night, fearful of running into a shadowy specter in the hallway.”

Spiritual Content

- DePrince and her family are Muslim, and to learn to read and write, DePrince would be “outside, sitting cross-legged on a grass mat, studying and writing my letters, which I copied from the Qur’an.”

- DePrince notes how loving her parents are and says that at night she would “thank Allah because I had been born into the house on the right, rather than the one on the left,” meaning the one where her uncle beat her cousins.

- DePrince’s mother notes that the debils (rebels of the Revolutionary United Front in Sierra Leone) spared DePrince’s family’s home and their lives when they burned the crops. Her mother then says, “We should be grateful to Allah for that.”

- When DePrince’s father died, she and her mom had to move into Uncle Abdullah’s house because “according to Sharia, Muslim law, Uncle Abdullah became our guardian.”

- Uncle Abdullah often refers to DePrince as the “devil child” because she could read several languages and had vitiligo, the condition that causes patches of her skin to lose coloration.

- DePrince was knitting a scarf for her brother, Teddy, when he passed away from complications with hemophilia. DePrince said, “What should I do with this? I was knitting it to go with Teddy’s favorite hoodie. I wanted to give it to him for Hanukkah.”

- DePrince had the opportunity to travel to Jerusalem where she “left a prayer for her [mother] in the chinks of the Wailing Wall, and [DePrince] wore [her] hamesh (or hamsa), a hand-shaped charm, for protection during our travels to the Dome of the Rock and the salty Dead Sea.” The reason why DePrince wears it is because “Muslims believe that it represents the hand of Fatima, the daughter of Mohammed, and Jews believe that it represents the hand of Miriam, the sister of Moses.”

- DePrince’s mom explains to DePrince the story of Moses. She says that “thousands of years ago, when the pharaoh was killing Jewish baby boys, Miriam had watched over her baby brother, Moses, after their mother floated him down the Nile River to protect him from the pharaoh’s wrath. He was then found by the pharaoh’s daughter and raised as a son of Egypt.”

by Alli Kestler

“There will come a day when these girls will no longer be a part of your life, and you’ll no longer care about what they once said about you,” Elaine DePrince. —Taking Flight

Latest Reviews

The Terror of the Southlands

Wrath of the Exiles

Jasmine Toguchi, Drummer Girl

The Pout-Pout Fish Goes to School

The Brink of War

Get Well, Crabby

The Pet Store Sprite

Stacey’s Remarkable Books

Lucy Maud Montgomery: A Writer’s Life