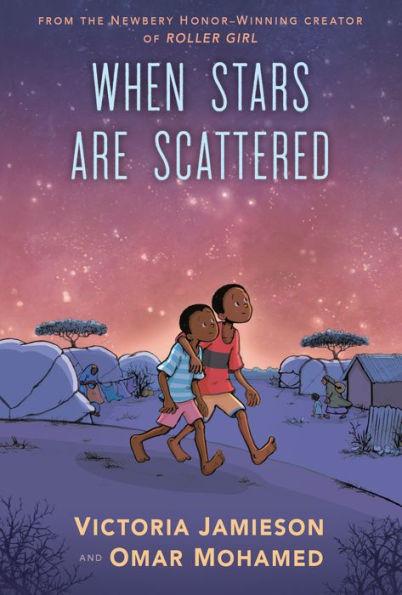

Omar and his younger brother Hassan have spent most of their childhood inside the A2 block of the Kenyan refugee camp Dadaab. After fleeing from his family farm in Somalia and becoming separated from his mother, Omar’s main concern is always protecting his only remaining family member, his nonverbal brother Hassan. Not only does Omar shield Hassan from the grueling chores of finding water and cleaning the tent, but he also cares for his brother when Hassan suffers seizures, or when he is teased by the other kids for only saying one word: Hooyo—“Mamma.” Omar also hopes one day his mother will find him and Hassan, and so he keeps all days the same. So, when Omar has the opportunity to go to school, he knows it might be a chance to change their future…but it would also mean leaving his brother, his only remaining family member, every day.

When Stars are Scattered is an easy-to-read, beautifully illustrated graphic novel. Omar Mohamed’s story comes to life in this graphic novel about his childhood in a refugee camp. The story shows the heartbreaking events that lead to Omar going to a refugee camp when he was only four. Omar’s story chronicles the hunger, heartbreak, and harsh conditions he endured. The story also sheds light on other issues including women’s access to education, starvation, family loss, and the constantly looming struggle to get on the UN list that invites refugees to interview for resettlement. Despite difficulties, Omar is still able to create a sense of family and home in the midst of difficult situations.

Like all people, Omar is a complex character who struggles to make the right decisions. He also often has conflicting emotions. For example, Omar wonders if his mother is dead or alive. He thinks, “I love my mom, but sometimes I hate her for leaving us. It’s like these two feelings are tearing me apart.”

At one point, Omar wonders if school is a waste of time; however, his foster mom tells him, “Prepare yourself and educate yourself. So you can be ready when God reveals his plan to you.” Eventually,

Omar falls in love with the power of learning and the potential of resettlement. Omar begins to learn what it feels like to build a new life by focusing on what he is given, rather than remaining torn by what he has lost. It is in this way that Omar moves from searching the stars for his mother to actually feeling that, “Many years ago, we lost our mother. But maybe she is not gone. She is in the love that surrounds us and the people who care for us.”

The story teaches several important life lessons including not to judge others and to make the most of your life. Appreciating what you have is the overarching theme of When Stars Are Scattered. Omar’s best friend tells him, “I didn’t ask for this limp. But I didn’t ask to live in a refugee camp either. . . I guess you just have to appreciate the good parts and make the most of what you’ve got.” Despite his struggles, Omar makes the most of what he has been given and thanks God for the love of others.

Based upon the real-life story of Omar Mohamed, When Stars Are Scattered navigates themes of familial loss, grief, struggle, and finally, hope, all while addressing the permanent feeling of a temporary refugee camp and the heartbreak of a war-torn home country. Omar shares his story because he wants to encourage others to never give up on home. Omar says, “Things may seem impossible, but if you keep working hard and believing in yourself, you can overcome anything in your path.”

When Stars Are Scattered not only encourages others to remain persistent, but also sheds light on the conditions of the refugee camps without getting into a political debate on immigration. Instead, the graphic novel focuses on Omar’s story—his hardships, his hopes, his despair, and his desire to help others like him.

The narrative is occasionally intense and heavy in its consideration of grief and the lifestyle of a refugee, which may upset younger readers. However, the serious and very important subjects that When Stars are Scattered covers are overall presented in a digestible way for young readers. The graphics that illustrate the story are absolutely captivating for all, while the humor and uplifting optimism that perseveres throughout this novel can fill the hearts of any audience.

Sexual Content

- Maryam’s family needs the money, so they allow Maryam to get married despite the fact that she is only in middle school. “Maryam’s husband is old, but he’s not too strict.”

Violence

- When Hassan hugs a boy, the boy pushes him away. The boy tells Omar, “I don’t know why you bother taking care of this moron. He’s a waste of space. You should let him wander off into the bush to get eaten by lions.” Omar punches the boy, and they get into a fight. An older woman breaks up the fight.

- While Omar is at school, Hassan wanders off and some kids “[take] his clothes, and… He’s pretty badly hurt.”

- When Omar’s best friend says he’s going to America, Omar thinks about the resettlement process. He thinks, “I heard about one guy… His case was rejected by the UN and he couldn’t handle it. He… He killed himself.”

- During an interview with the United Nations, Omar talks about the village he came from. Omar was playing under a tree when he heard men yelling at his father. Then, “Bang! Bang! Bang!” Omar ran to his mother, who told Omar to take his brother and run to the neighbor. The neighbor hides them inside, but “then I heard gunshots and screaming, and soon the whole village was running. There were angry men everywhere.” Omar and his brother run and stay with the people from the village, but they never see their mother again. The event is described over three pages.

- When Fatuma describes her sons, she notes that “they were killed in Somalia” but there is not any explicit description as to how they were killed.

- When Hassan tries to help Omar with collecting water one day, Omar gets frustrated and shoves Hassan, yelling “leave me alone!”

Drugs and Alcohol

- Some of the men in the refugee camp chew khat leaves. Omar explains that “a lot of men in camp chew Khat. They say it kind of helps you . . . forget things.”

Language

- There are multiple times where some of the children are called by names based upon their physical appearance. For example, one child is called “Limpy” based upon a physical disability. Omar is also called “Dantey” for being quiet.

- The story has some mild name-calling, such as idiot, jerk, and dodo head. For example, Omar thinks that one of the boys his age is “kind of a jerk.”

- While walking to school, someone yells at two girls, “Hey it’s the mouse and the shrimp.” In reply, someone says, “Tall Ali… You’re like… A towering tree of an idiot.”

- In class among the girls, A boy says, “You’re just jealous because you’re, what, number seventeen? I didn’t know we had seventeen girls in class. My goat could’ve done better than you.”

- When Tall Ali becomes frustrated at Hassan for not understanding a game, he says to Omar, “ I don’t know why you bother taking care of this moron! He’s a waste of space. You should let him wander off into the bush to get eaten by lions!” Then he says to both Omar and Hassan, “Now I know why you’re orphans. That’s probably why your mom left you.”

- When Jeri gives a presentation in school about how much he wants to be a teacher when he grows up, another classmate exclaims, “what a kiss-up.”

- When Omar learns that all the teachers speak in English, he thinks, “Oh crud.”

Supernatural

Spiritual Content

- When community leader Tall Salan tries to convince Omar to go to school, he says, “Omar, only God knows what will happen in the future.” Omar’s foster mom Fatuma also says, “I think you should look deep inside yourself and see what God is telling you to do. If this is God’s will, then He will make everything okay.”

- Omar and his brother practice Islam. Because of this, Omar recognizes that “Like every morning, I hear the call to morning prayers over the loudspeakers. It’s early, but today I was already awake.” There is also a chapter dedicated to discussing the Holy Month of Ramadan. This chapter shows Omar and his friends celebrating Eid Al-Fitr, which is the holiday at the end of this month. It is also recognized that Omar’s camp, and others near it, have a “loudspeaker that, five times a day, called everyone to prayer.”

- When Omar decides to go to school, he prays “that [he’s] making the right decision.”

- Omar’s foster mom tells him that God has given Hassan gifts. “Hassan is considerate, helpful, and friendly.”

- When the community comes together to help Hassan, Omar thinks, “We may be refugees and orphans, but we are not alone. God has given us the gift of love.”

- During Ramadan, the Muslim holy month, Muslims are supposed to fast from sunrise to sunset. Even though many in the refugee camp are always hungry, “people in the camp fast anyway… Just because we’re poor and hungry doesn’t mean we can’t observe the holy month.”

- During Eid, Omar prays “for me and Hassan. That we’ll find a way out of this refugee camp—that someday we will find a home.”

- When a social worker brings Omar a school uniform, he thinks, “you just try your best, and God will find a way to help you when you need it.”

- Even though life has dark moments, Omar believes that “God will deliver an answer, and you’ll find a faith out of the darkness. The kindness of strangers. The promise of new friends.”

- When Omar is waiting to see if he will be resettled in America, he thinks, “We’ve done all we can. It’s in God’s hands now.”

by Hannah Olsson